In just one cow, there are dozens of cuts waiting to make it to your dinner table, and all of them are different thanks to where they are on the cow. The degree of tenderness, flavor and color are based on the type cow: whether it was factory farmed or grass-fed in pasture, whether the particular muscle was well-worked or hardly used, how a butcher chooses to cut the meat, and more.

Naturally, the average consumer might be mystified by the massive variety of beef cuts, and even more confused about how best to prepare and cook them. We’ve got you covered. With help from praised Orange County, California, chef Aron Habiger, we’ve compiled the definitive guide to different cuts of beef and how to cook them next time you’re in the kitchen (or outside grilling!)

All cuts of beef, when inspected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), are subject to a grading system. Three main categories comprise the grading system—prime, choice and select—with consideration toward the “palatability” of the meat, i.e., the tenderness, juiciness, and flavor. Generally, Americans gobble up meat from the “select” category—the cheapest and least decadent of the three (there are also subpar lower rungs like standard, commercial and utility). Prime beef comprises less than two percent of all USDA-inspected beef, and restaurant purveyors and suppliers buy most of it. Choice falls between the two extremes. As you’ll learn, there are some cuts where you’ll want to shell out for the highest quality. [tweet_quote] Prime beef is the most decadent of graded meat, and comprises under 2% of all USDA-inspected beef. [/tweet_quote]

With traditional “steak cuts”—top sirloin, New York strip, ribeye, and porterhouse—there are some universal quality indicators. Look for marbling, the consistent speckling of white intramuscular fat. The more marbling, the richer the meat. Make sure the steaks aren’t broken from too much man-handling. Finally, all beef cuts should smell clean—“like nothing but a light beefy scent,” Habiger says.

Below, you’ll find all the major cuts of beef, and, most importantly, how to cook and season them to perfection.

Top Sirloin

Related cuts: Coulotte steak, top sirloin butt steak

Where it is on the cow: Top sirloin steak—cut from the sirloin, or “above the loin” portion of the cow—makes for a great introduction to traditional steak preparation.

What it is: If you’re cooking up a couple of steaks at home for the first time, we recommend the top sirloin. It’s lean but still flavorful and decently tender when prepared properly. Typically much cheaper than its first-rate cousins like New York strip or the ribeye, you’ll appreciate its versatility and won’t sob too hard if you overcook it slightly.

How to cook it: Searing steak in a hissing-hot cast iron pan with lots of fat (grass-fed butter, ghee or clarified butter, tallow and coconut oil are all Paleo-friendly options) is almost always a good idea. Top sirloins, however, take well to the grill—just take care not to overcook them.

How to season it: You can season traditional steaks with spice rubs that include garlic, paprika, red pepper flakes, coriander and more—we know you’ve seen various rubs and spice mixes on the spice aisle—but beef enthusiasts opt to season their steaks with only a liberal sprinkling of quality sea salt. And no, we didn’t forget the pepper: It’s just better to “finish” your steak with fresh pepper, as it’s a fragile spice, rather than burn it in the cooking process.

More tips: Always let your steak come to room temperature before cooking it and let it rest afterward. It’s a critical tip home cooks often overlook.

If you’re serving up top sirloin, keep the steak neutral and save the aggressive seasoning for your accompanying vegetables—try roasted green varieties like asparagus, broccoli or zucchini.

New York Strip

Where it is on the cow: Cut from the top loin portion of the cow, New York strips are typically boneless (unless you’re dealing with a unique cut). The strip is cut from a little-worked muscle (the longissimus, if you want to get technical), leaving it very tender.

What it is: Compared to top sirloin steak, the New York strip ups the ante, though it’s not yet in the big leagues—that’s saved for the ribeye and porterhouse. It’s also deeply flavorful and succulent thanks to its fat cap. Don’t trim that too much if you’re looking for flavor.

How to cook it: All of the steak preparation rules of the top sirloin remain true with the New York strip. It takes well to a cast-iron pan, but grilling is an option too.

How to season it: Keep seasoning subtle—salt and a finishing of pepper always work—though you can try a finishing sauce or compound butter or oil (a mélange of fresh herbs and fat) if you’d like.

More tips: If you’re looking to get fancy, Chef Habiger recommends rendering some of the New York strip’s fat into tallow, then basting the steak in it as you cook.

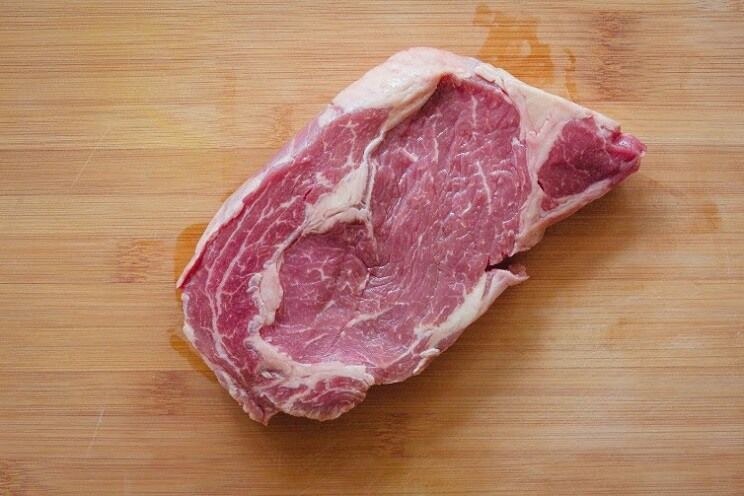

Ribeye

Related cuts: Delmonico steak, Spencer steak, market steak

Where it is on the cow: As the name suggests, ribeye steaks are cut from the rib portion of the cow—traditionally the best center portion, or the “eye,” of the entire rib steak.

What it is: Ribeye steaks are sold both bone-in and bone-out, though traditionally it’s a “rib steak” if the bone is still attached. Ribeye steaks are typically large and dotted with consistent white specks of intramuscular fat known as marbling. This marbling is thanks to the lightly used muscle in the upper rib section. Marbling makes for a gloriously rich beef flavor and melt-in-your-mouth tenderness. Chefs—and our bellies—love ribeye steaks for this reason.

How to cook it: Sear the steak in a cast-iron skillet until a crust forms on both sides. Alternatively, grill it for 5 to 6 minutes per side.

How to season it: It’s especially important to keep ribeye prep and seasoning simple with just salt and pepper—you’re paying for that rich beef flavor, so let it shine.

More tips: Habiger recommends serving ribeye steaks alongside a parsnip puree as a lighter alternative to ultra-heavy potatoes.

T-Bone

Related cuts: Porterhouse

Where it is on the cow: T-bone steaks and porterhouses are very similar. Both are cut from the short loin and include a strip steak on one side of the bone with the tenderloin on the other side. T-bone steaks are cut slightly differently with a smaller piece of the tenderloin. As the name suggests, the tenderloin is the most tender portion of the cow because it gets very little use.

What it is: Habiger calls porterhouse steaks the “Cadillac” of all steak cuts, and for good reason. They’ll nearly always be the most expensive steak on the menu, and not just because they’re ginormous cuts of steak that are better suited for sharing. The combination of rich beef strip and ultra-soft tenderloin makes the porterhouse the best of both worlds.

How to cook it: Use your cast-iron skillet and some fat to form a good crust on the steak. You can use your oven to finish cooking the inside of a porterhouse.

How to season it: Go heavy on the salt with a porterhouse—a cut of steak that thick can take it.

More tips: For the love of God, don’t forget to let your porterhouse come to room temperature and rest. You spent a pretty penny on it.

Filet Mignon

Related cuts: beef tenderloin

Where it is on the cow: Filet mignon is cut from the smallest end of the tenderloin—this section gets hardly any use, and thus lacks connective tissue. This results in steak so tender it melts like butter in your mouth, but the flavor is relatively one-dimensional.

What it is: Filet mignon is known as the height of “fancy” steak, though Habiger notes that true steak lovers aren’t as impressed with it.

How to cook it: Searing filet mignon in a cast-iron skillet is still the way to go. While other steak cuts are best served medium-rare, filet mignon tends to be served on the rare side.

How to season it: Because the flavor tends to be one note, filet mignons need more aggressive flavorings. Serve them with a peppercorn sauce, red wine reduction or cream sauce.

More tips: You can wrap filet mignons in bacon to add much needed fat and moisture.

Minute Steak

Related cuts: sandwich steak, cube steak, round steak, breakfast steak

Where it is on the cow: Minute steak and its many-named variants are typically cut from the rear leg, or “round portion” of the cow, as well as from the sirloin area. Given that the area is constituted by strongly-worked muscles, there’s very little fat to be found.

What it is: You may have noticed by now that steak naming is a fairly straightforward process. Thus, it makes sense that minute steak is a generic term for thinly cut beef that cooks within minutes. It can either be sold thinly sliced or thinly sliced and tenderized with a mallet, leaving it with the characteristic mini-cubed indentation.

How to cook it: Pan frying or griddle frying is the way to go for these quick-cooking cuts.

How to season it: Such thinly sliced steak takes well to Paleo-friendly breading and crusts—think Paleo chicken fried steak.

More tips: Minute steak can also be quickly sliced and added to stir-fry for an Asian-inspired dish.

Tri-tip Steak

Related cuts: triangle steak

Where it is on the cow: Tri-tip, cut from the bottom sirloin portion of the cow, is a triangular cut of muscle that’s relatively lean but still deeply flavorful.

What it is: It’s a full-flavored inexpensive cut, and takes well to low and slow cooking.

How to cook it: You’re probably most familiar with barbequed tri-trip—and that’s where it shines. You can also oven roast trip at a low and slow pace for deep flavor.

How to season it: Here is where you want to put your spice cabinet to use. Try a dry rub filled with chili powder, garlic, salt, pepper, cumin, coriander and paprika.

More tips: If you opt for the “sit and seep” method, where you let the dry rub infuse throughout the steak for many hours, omit the salt—it will dry your hunk of meat out.

Skirt Steak

Related cuts: flank steak, hanger steak

Where it is on the cow: Cut from the bottom plate of the cow, skirt steak is heavy on flavor and light on tenderness. Hanger steak is cut from the same region, but it’s a bit tenderer and even deeper in flavor. Flank steak is cut from the adjacent flank of the cow—another well-worked area, though it’s flavor is mildly different.

What it is: What do all three have in common? They’re all at their best when thoroughly marinated, then flash cooked to rare or medium-rare to avoid toughness.

How to cook it: Flash cooking on a grill or in a pan keeps these cuts from becoming tough. Quick cooking vegetables like bell peppers and onions pair well here.

How to season it: These cuts take well to aggressive marinades with acidic elements, like chimichurri sauce, carne asada marinade, fajitas marinade and stir-fry sauce.

More tips: These cuts tend to be inexpensive and therefore need a little more work. Be sure to trim them of their tough membranes and silver skin.

These cuts can also be rolled around vegetables for Paleo-friendly wraps.

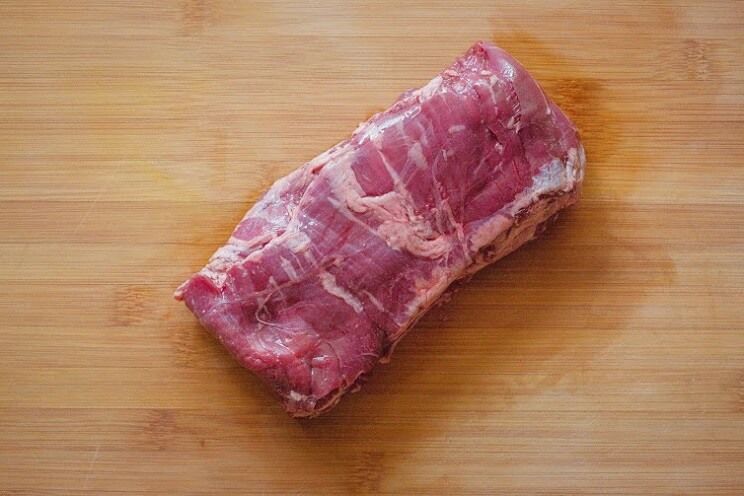

Chuck Steak

Related cuts: top round, rump roast, flat iron steak

Where it is on the cow: Cut from the chuck portion of the cow all the way in the front, chuck steak and its variants tend to be sold as large rectangular roasts. A well-worked area, the chuck contains a lot of collagen and connective tissue.

What it is: Chuck meat is often sold as stew meat. It’s also the most popular cut for ground beef.

How to cook it: When sold as a “roast,” chuck meat requires low and slow cooking. One-pan and crock-pot stews are the preferred method for this cut. Cube chuck steak and sear it in a Dutch oven with some coconut oil until it’s formed a crust, then add your stewing ingredients.

How to season it: There are so many varieties of stewing flavors: try paprika-heavy Hungarian goulash or a meaty Indian curry.

More tips: Opt for starchy root vegetables like carrots, sweet potatoes and parsnips in a stew—they’ll hold up best to your low and slow preparation.

Beef Brisket

Related cuts: brisket flat cut

Where it is on the cow: Found in the lower chest of the cow, brisket has a lot of collagen and connective tissue from supporting its standing weight.

What it is: A fabulous choice for barbeque, beef brisket benefits from a slow cooking to break down the muscle fibers for an extremely tender cut of meat.

How to cook it: Slowly smoke brisket over low coals for about six hours, basting occasionally with accumulated juices. You can also use a charcoal grill for similar indirect cooking.

How to season it: Smoked meat works great with a sweet component. Try a straightforward spice rub with brown sugar, chili powder, cumin, coarse salt and black pepper.

More tips: For an extra juicy brisket, brush every hour or so with a beer-based mop sauce. Coffee is a great addition to the mop sauce, too!

Want to start cooking with some of the best meat in the country? Check out US Wellness Meats and use our exclusive PaleoHacks coupon below!

(Read This Next: 7 Crucial Ways to Tell if Your Meat is Paleo or Not)

Fiber-Rich Plantain Chips

Fiber-Rich Plantain Chips

Show Comments